HPV vaccination: a safe and effective way to protect against HPV related cancers for girls and boys?

You are here

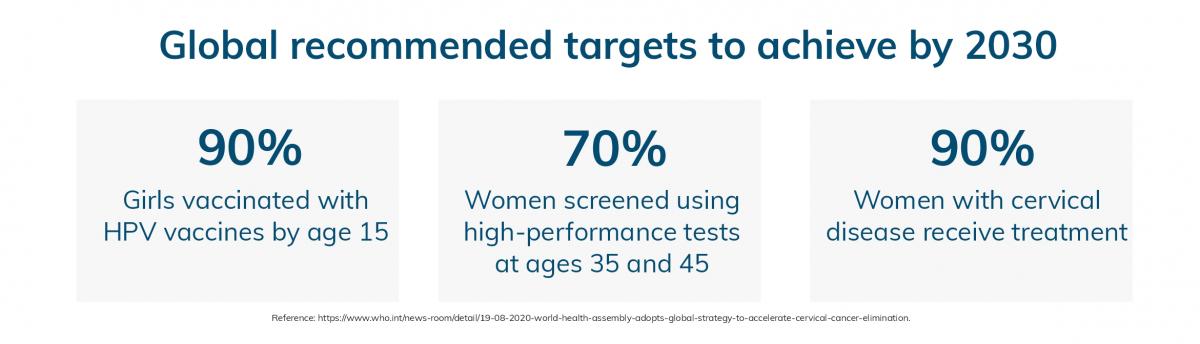

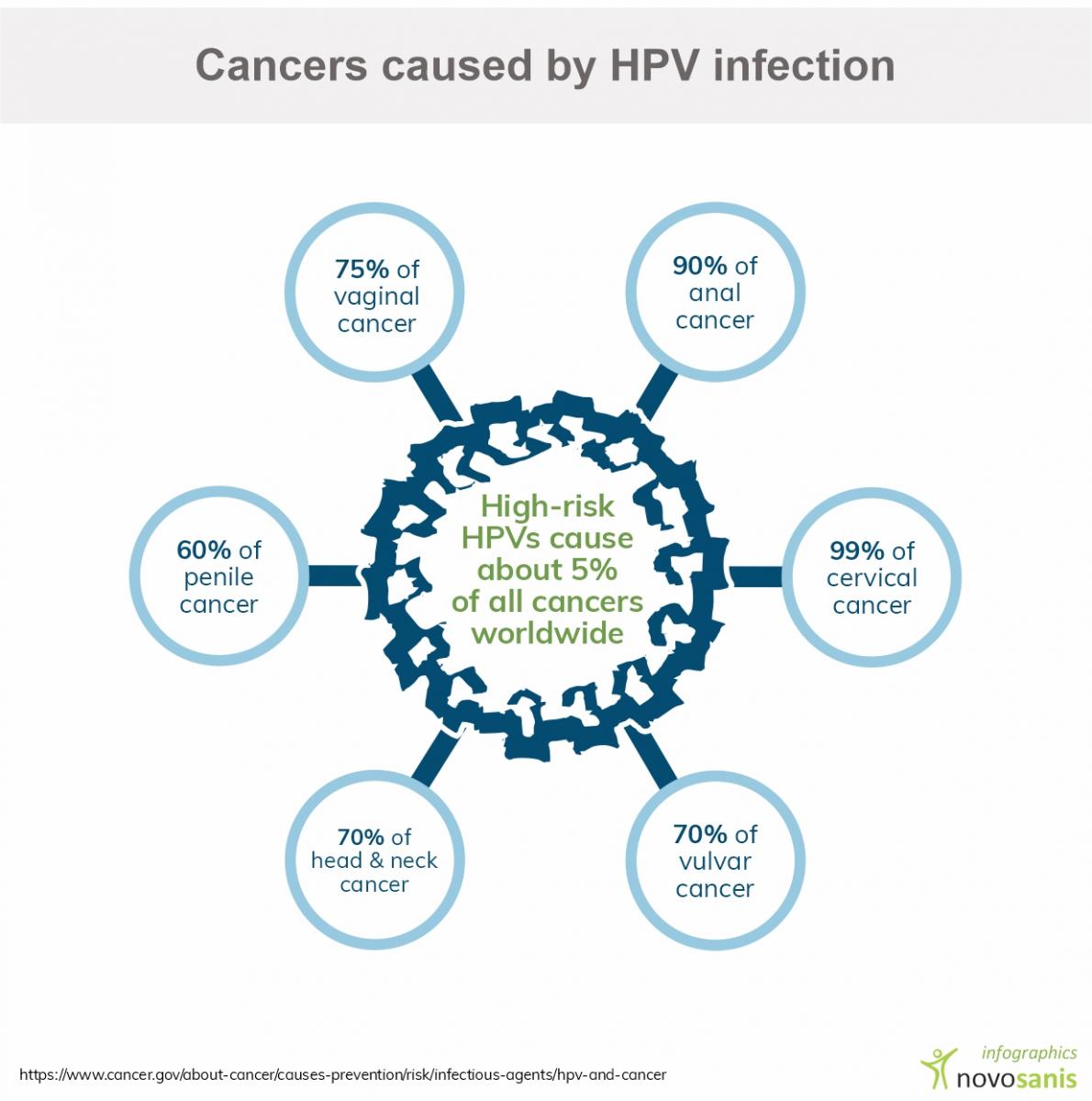

Particular strains of Human Papillomavirus (HPV), such as high-risk types can cause changes in cell DNA, leading to various cancers. Consequently, protecting against HPV infections, through vaccination is critical and can reduce the risk of HPV related cancer development1. The HPV vaccine is safe and effective, and is primarily used for young girls, but is also recommended for boys aged 12-131,2. Implementation of vaccination against HPV with a high coverage supports the global strategy devised to achieve the elimination of cervical cancer.

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and its link to cancer

HPV infections affect the skin and/or lining of cells inside the body. In most people, the infection causes no harm, and disappears naturally overtime. However, HPV strains such as HPV16 and 18 are known to be a major cause of cervical cancer in women. A high percentage of penile and anal cancers have also been linked to HPV163. In certain high-risk groups, such as men who have sex with men (MSM) as well as HIV-positive individuals, an even higher prevalence of anal infections are related to HPV4.

Vaccine impact studies

The benefits of HPV vaccination for women in cervical cancer prevention is well-researched. National HPV vaccination programs are implemented in many high-income countries since 20105. Developing countries, such as Bhutan (2010) and Rwanda (2011) were also among the first countries in Asia and Africa respectively to roll-out HPV vaccination programs for school girls5.

However, in several developing countries, HPV vaccines are still not widely available, and many women are unaware of their benefits6. Therefore, vaccine impact studies that highlight the benefits and potential of vaccination on a population could help create more awareness and reach a wider group.

Urine as sample type to monitor HPV vaccine effectiveness

In this regard, urine, as a sample type offers an easy and simple approach. A lot of evidence shows that HPV DNA can be found in urine, in particular in first-void urine (first 20ml of urine flow)7. Using this knowledge further, researchers carried out studies in Bhutan and Rwanda to monitor the effectiveness of HPV vaccination5,8.

HPV urine surveys were conducted in both countries with around 1,000 girls. Participants self-collected a urine sample using Novosanis’ urine-capturing device, Colli-Pee®, suited to capture first-void urine. The results concluded that HPV presence in urine was associated with sexual activity. In both Bhutan and Rwanda HPV6/11/16/18 prevalence was lower in vaccinated than in unvaccinated participants5, highlighting the importance of vaccination.

A follow up study revealed the urine-based survey approach used in Rwanda and Bhutan to monitor the impact of HPV vaccination is well-accepted and remarkably adaptable to a wide range of settings and populations, making this approach particularly valuable to periodically assess the early impact of HPV vaccination8.

Despite the potential benefits, HPV vaccination in boys is currently only available in a few countries. More than 70 countries, including 33 belonging to the WHO European Region, have introduced HPV vaccination into their national immunization programs for girls, and 11 countries have done so for boys. The EU guidelines recommend all European countries to include actions to achieve population-based HPV vaccination of girls, as well as vaccination of boys if cost-effective.

The impact of extending HPV vaccination programs across all genders vaccinating has the potential to reduce the burden of HPV as well as prevent many HPV-linked conditions9.

Read our white papers on HPV screening for cervical cancer

- Cancer Research UK - Does HPV cause cancer? - https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/infection...

- CDC Features - HPV Vaccine is Cancer Prevention for Boys, Too! []. USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018 December. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/features/hpvvaccineboys/index.html

- Harder T, Wichmann O, Klug SJ, van der Sande MAB, Wiese-Posselt M. Efficacy, effectiveness and safety of vaccination against human papillomavirus in males: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2018 Jul 18;16(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1098-3. Review. PubMed PMID: 30016957

- Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, May 2017. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017 May 12;92(19):241-68. PubMed PMID: 28530369

- Franceschi S, Chantal Umulisa M, Tshomo U, Gheit T, Baussano I, Tenet V, Tshokey T, Gatera M, Ngabo F, Van Damme P, et al. Urine testing to monitor the impact of HPV vaccination in Bhutan and Rwanda. Int J Cancer. 2016 Aug 1;139(3):518-26. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30092. Epub 2016 Apr 15. PubMed PMID: 26991686.

- Graham JE, Mishra A. Global challenges of implementing human papillomavirus vaccines. Int J Equity Health. 2011 Jun 30;10:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-27. PubMed PMID: 21718495

- Vorsters A, Van Keer S, Van Damme P. The use of urine in the follow-up of HPV vaccine trials. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(2):350-2. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.995058. PubMed PMID: 25664398

- Fappani C, Bianchi S, Panatto D, Petrelli F, Colzani D, Scuri S, Gori M, Amendola A, Grappasonni I, Tanzi E, Amicizia D. HPV Type-Specific Prevalence a Decade after the Implementation of the Vaccination Program: Results from a Pilot Study. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Apr 1;9(4):336. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040336. PMID: 33916132

- Green A. HPV vaccine to be offered to boys in England. Lancet. 2018 Aug 4;392(10145):374. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31728-8. Epub 2018 Aug 2. PubMed PMID: 30152370.